Cultural erasure

Tracing the destruction of Uyghur and Islamic spaces in Xinjiang

This report is supported by a companion website, the Xinjiang Data Project.

What’s the problem?

The Chinese Government has embarked on a systematic and intentional campaign to rewrite the cultural heritage of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). It’s seeking to erode and redefine the culture of the Uyghurs and other Turkic-speaking communities—stripping away any Islamic, transnational or autonomous elements—in order to render those indigenous cultural traditions subservient to the ‘Chinese nation’.

Using satellite imagery, we estimate that approximately 16,000 mosques in Xinjiang (65% of the total) have been destroyed or damaged as a result of government policies, mostly since 2017. An estimated 8,500 have been demolished outright, and, for the most part, the land on which those razed mosques once sat remains vacant. A further 30% of important Islamic sacred sites (shrines, cemeteries and pilgrimage routes, including many protected under Chinese law) have been demolished across Xinjiang, mostly since 2017, and an additional 28% have been damaged or altered in some way.

Alongside other coercive efforts to re-engineer Uyghur social and cultural life by transforming or eliminating Uyghurs’ language, music, homes and even diets,1 the Chinese Government’s policies are actively erasing and altering key elements of their tangible cultural heritage.

Many international organisations and foreign governments have turned a blind eye. The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) have remained silent in the face of mounting evidence of cultural destruction in Xinjiang. Muslim-majority countries, in particular, have failed to challenge the Chinese Government over its efforts to domesticate, sinicise and separate Uyghur culture from the wider Islamic world.

What’s the solution?

The Chinese Government must abide by Article 4 of China’s Constitution and allow the indigenous communities of Xinjiang to preserve their own cultural heritage and uphold the freedom of religious belief outlined in Article 36. It must abide by the autonomous rights of minority communities to protect their own cultural heritage under the 1984 Law on Regional Ethnic Autonomy.

UNESCO and ICOMOS should immediately investigate the state of Uyghur and Islamic cultural heritage in Xinjiang and, if the Chinese Government is found to be in violation of the spirit of both organisations, it should be appropriately sanctioned.

Governments throughout the world must speak out and pressure the Chinese Government to end its campaign of cultural erasure in Xinjiang, and consider sanctions or even the boycotting of major cultural events held in China, including sporting events such as the 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

The UN must act on the September 2020 recommendation by a global coalition of 321 civil society groups from 60 countries to urgently create an independent international mechanism to address the Chinese Government’s human rights violations, including in Xinjiang.2

Executive summary

Under President Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has adopted a more interventionist approach to nation building along China’s ethnic periphery. Indigenous non-Han cultures, which are considered backward, uncivilised and now potentially dangerous by CCP leaders, must yield to the Han normative centre in the name of an ostensibly unmarked ‘Chinese’ (中华) culture.3

The deliberate erasure of tangible elements of indigenous Uyghur and Islamic culture in Xinjiang appears to be a centrally driven yet locally implemented policy, the ultimate aim of which is the ‘sinicisation’ (中国化) of indigenous cultures, and ultimately, the complete ‘transformation’ (转化) of the Uyghur community’s thoughts and behaviour.

In work for this report, we sought to quantify the extent of the erasure and alteration of tangible indigenous cultural heritage in Xinjiang through the creation of two new datasets recording:

- demolition of or damage to mosques; and

- demolition of or damage to important religious–cultural sites, including shrines (mazars), cemeteries and pilgrimage routes.

With both the datasets, we sought to compare the situation before and after early 2017, when the Chinese Government embarked on its new campaign of repression and ‘re-education’ across Xinjiang.

Media and non-government organisation reports have unearthed individual examples of the deliberate destruction of mosques and culturally significant sites in recent years.4 Our analysis found that such destruction is likely to be more widespread than reported, and that an estimated one in three mosques in Xinjiang has been demolished, mostly since 2017.

This equates to roughly 8,450 mosques (±4%) destroyed across Xinjiang, and a further estimated 7,550 mosques (±3.95%) have been damaged or ‘rectified’ to remove Islamic-style architecture and symbols. Cultural destruction often masquerades as restoration or renovation work in Xinjiang. Despite repeated claims that Xinjiang has more than 24,000 mosques5 and that the Chinese Government is ‘committed to protecting its citizens’ freedom of religious belief while respecting and protecting religious cultures’,6 we estimate that there are currently fewer than 15,500 mosques in Xinjiang (including more than 7,500 that have been damaged to some extent). This is the lowest number since the Cultural Revolution, when fewer than 3,000 mosques remained (Figure 1).7

Figure 1: The number of mosques in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region since its founding

Note: The estimates from our research are included as the 2020 datapoint. Mosques that have been damaged but not destroyed are shown in orange. Source: Li Xiaoxia (李晓霞), ‘Analysis on the quantity change and management policy of Xinjiang mosques’ (新疆清真寺的数量变化及管理政策分析), Sociology of Ethnicity (民族社会学研究通讯), vol. 164 (2018), p. 40, online; and ASPI analysis.

Mosques across Xinjiang were rebuilt following the Cultural Revolution, and some were significantly renovated between 2012 and 2016, including by the construction of Arab- and Islamic-style domes and minarets. However, immediately after, beginning in 2016, government authorities embarked on a systematic campaign to ‘rectify’ and in many cases outright demolish mosques.

Areas visited by large numbers of tourists are an exception to this trend in the rest of Xinjiang: in the regional capital, Urumqi, and in the city of Kashgar, almost all mosques remain structurally intact.

Most of the sites where mosques were demolished haven’t been rebuilt or repurposed and remain vacant. We present three case studies (on the renovation and demolition of mosques in northern Xinjiang, the land use of demolished mosques, and the destruction of the Grand Mosque of Kargilik) to highlight the impacts of this process of erasure.

Besides mosques, Chinese Government authorities have also desecrated important sacred shrines, cemeteries and pilgrimage sites. Our data and analysis suggest that 30% of those sacred sites have been demolished, mostly since 2017. An additional 27.8% have been damaged in some way. In total, 17.4% of sites protected under Chinese law have been destroyed, and 61.8% of unprotected sites have been damaged or destroyed. We present two case studies (the destruction of the ancient pilgrimage route of Ordam Mazar and of Aksu’s sacred cemeteries) to show in detail the impact on sacred spaces.

Methodology

The Chinese Government’s 2004 Economic Census identified more than 72,000 officially registered religious sites across China, including more than 24,000 mosques in Xinjiang.8 Given the lack of access to Xinjiang and the sheer number of sites, we used satellite imagery to build a new dataset of pre-2017 mosques and sacred sites.

We found the precise coordinates of more than 900 sites before the 2017 crackdown, including 533 mosques and 382 shrines and other sacred sites.

Each of those sites was then cross-referenced against recent (2019–2020) satellite imagery and categorised as destroyed, significantly damaged, slightly damaged or undamaged. In most cases, significant damage relates to part of the site being destroyed or to Islamic-style architecture (such as domes and minarets) being removed.

We then used a sample-based methodology to make statistically robust estimates of the region-wide rates of destruction by cross-referencing it to data from the 2004 Economic Census, by prefecture.9

For prefectures for which we had a sample of more than 2.5% of mosques, the prefecture-wide destruction and damage rates were extrapolated directly from the observed sites in our sample.

The rate of destruction in prefectures that were undersampled (having less than 2.5% of all mosques located) was estimated by averaging the observed prefectural rate of destruction and the region-wide rate (excluding the regional capital, Urumqi). We estimated the total number of mosques destroyed and damaged by combining those prefectural-level extrapolations.

This analysis is only able to determine demolition or other visible structural changes to the sites. Based on our sample, the razing of mosques appears to have been carried out broadly across Xinjiang, and neither urban nor rural mosques were more likely to be damaged or demolished.

Urumqi and the tourist city of Kashgar are outliers where most mosque buildings remain visibly intact.

Those cities are frequented by domestic and international visitors and serve to conceal the broader destruction of Uyghur culture while curating the image of Xinjiang as a site of ‘cultural integration’ and ‘inter-ethnic mingling’.10

For more details on how our calculations were done and how to access the raw data, see the appendix to this report.

Results and case studies

Mosques

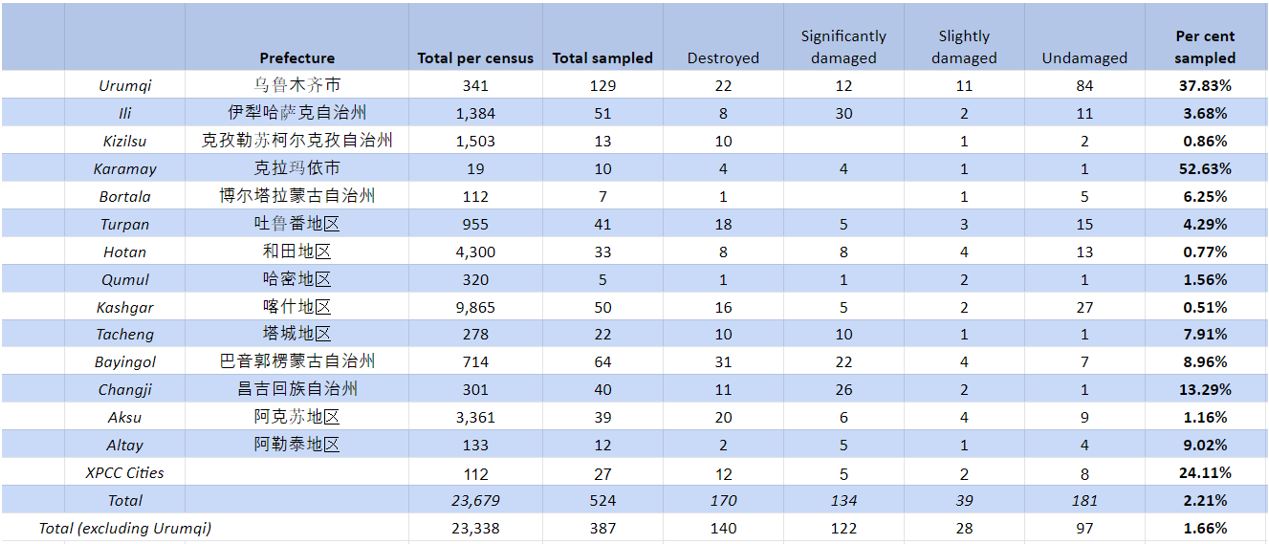

In total, we located and analysed a sample of 533 mosques across Xinjiang, including 129 from Urumqi. Of those mosques, 170 were destroyed (31.9%), 175 were damaged (32.8%) and 188 remained undamaged (35.3%). Urumqi has only 1.4% of Xinjiang’s mosques, despite representing 24% of our sample, and was an outlier that showed lower rates of mosque demolition (17% versus an average of 36% in other prefectures). Of the 404 mosques we sampled in other parts of Xinjiang, 148 were destroyed (36.6%), 152 were damaged (37.6%) and 104 were undamaged (25.8%). Figure 2 summarises the percentages of sampled mosques destroyed or damaged, by prefecture.

Figure 2: Percentage of sampled mosques that are damaged or destroyed, by prefecture, XUAR

Note: Territorial borders shown on maps in this report do not indicate acceptance by ASPI, in general they attempt to show current territorial control and not claims from any country. Source: ASPI ICPC.

The destruction of mosques appears to be correlated with the value authorities place on a region’s tourist potential; for example, Urumqi has a low rate of demolition, followed by the major tourist sites like Kashgar.11 Yet, it should be noted, both cities have undergone and continue to undergo significant urban development, which has resulted in the demolition or ‘renovation’ of part of Kashgar’s old city and the Uyghur-dominated Tengritagh and Saybagh districts of Urumqi.12

Extrapolating those figures on a prefectural level from official statistics allowed us to estimate the full number of destroyed and damaged mosques in Xinjiang. We found that across the XUAR approximately 16,000 mosques have been damaged or destroyed and 8,450 have been entirely demolished. The 95% confidence range of our regional findings is ±4% for the estimates of demolished, destroyed and undamaged mosque numbers. The full prefectural breakdown is shown in Table 1 and Figure 3.

Table 1: Full results showing the prefectural breakdown of mosques in Xinjiang, our sampling data and our estimates of damaged numbers

Note: In this table XPCC refers to the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Bingtuan), a government entity distinct to Xinjiang’s regional government that directly administers large areas of the XUAR. Source: ASPI ICPC.

Figure 3: The estimated number of mosques destroyed or damaged in each prefecture of the XUAR

Note: Red dots represent the estimated number of destroyed mosques, orange represents the estimated number of damaged mosques. The number written shows these two combined. For full details see Table 1. Source: ASPI ICPC.

Officials from the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have repeatedly claimed that Xinjiang has more than 24,000 mosques and cite that as evidence of the state’s respect for religious freedom.13

However, our analysis shows that in most prefectures a majority of mosques and other sites of Islamic worship are being destroyed or transformed in ways that erode their religious and cultural significance.

In June 2015, Yang Weiwei, a researcher at the official CCP school in the northern prefecture of Altay, clearly articulated one of the perceived threats that authorities believe mosques pose to social stability in Xinjiang.14 Without providing evidence, she asserted that ‘the number of mosques in Xinjiang far exceeds the needs of normal religious activities,’ and instead provide venues for separatists and extremists to proselytise. The Islamic faith of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang, she claimed, is propelling society away from traditional secularism towards conservatism, and challenging CCP rule. ‘In southern Xinjiang, the capacities of the party’s grassroot organs are hampered, but the role of mosques [is] constantly being strengthened,’ she warned.15

Her report specifically recommended that mosques be demolished, saying that only one mosque should exist in each administrative unit, that their design should adhere to strict unified standards (implying the removal of Islamic and Arab architecture), and that their opening hours should be limited to a single day every week and holidays.16

That recommendation doesn’t appear to be restricted to Altay Prefecture. Our evidence suggests the demolition and ‘rectification’ of mosques is more severe in other prefectures in Xinjiang, 17 of which (out of the 19 that we recorded) have higher rates of mosque demolition than Altay.

Xinjiang’s latest ‘mosque rectification’ (清真寺整改) campaign, which was conducted under the guise of improving public services and safety, began in 2016 and gathered pace under the new Xinjiang Party Secretary, Chen Quanguo.17 Local authorities were responding in part to Xi Jinping’s call for the ‘sinification’ (中国化) and the ‘deradicalisation’ (去极端化) of religion in Xinjiang.18 The vast majority of mosques in our sample that remained undamaged had no existing visible Islamic architectural features and didn’t need modification to adhere to the strict standards set out by the regional ‘rectification’ campaign.

Additionally, media reports suggest that a number of mosques that remain physically intact (and therefore would be classified as undamaged in our dataset) have been secularised or converted into commercial or civic spaces, including cafe-bars19 and even public toilets.20 We aren’t able to quantify this practice using our methodology.

However, visitors to the region since 2017, who saw several still-standing mosques and spoke privately with ASPI, estimated that roughly 75% of the mosques still standing had either been padlocked shut and had no worshippers visiting at key prayer times or had been converted into other uses. A separate recent visitor to Kashgar city told us that ‘virtually all’ of the mosques in the ‘old city’ had been closed and that a limited number had been converted into cafes.

Although other religious minorities aren’t the focus of our report, we also checked several Christian churches and Buddhist temples across Xinjiang and found that none of those sampled had been damaged or destroyed. This contrasts with the high number of damaged and destroyed mosques across the region, along with the widespread ‘rectification’ of many religious sites in other parts of China.21

Case study: Northern Xinjiang’s renovations and demolitions

Our study of mosques in northern Xinjiang revealed a wave of renovations and reconstructions between 2012 and 2016, followed by a wave of demolitions from 2016 onwards. This sudden reversal coincided with significant national-level changes to religious policy and a crackdown on expressions of faith,22 suggesting a centrally driven policy directive rather than decisions by local officials.

We found evidence that most mosques in a number of prefectures had been standardised through the addition of a large central dome and minarets on each building’s corners before 2016. An example of four mosques that were standardised in the same way is shown below in figures 4 and 5. For example, the bottom-left mosque in the examples is a mosque in Shiho city (Wusu). A dome and minarets were added in mid-2015, but by mid-2018 the entire site had been demolished.

Figure 4: Four mosques in Northern Xinjiang, chosen at random from our database, showing their structure before renovation between 2012 and 2016

Note: Clockwise from top left their locations are in Dorbijin County (Emin - 46.522N, 83.648E), Qutubi County (Hutubi - 44.185N, 86.900E), Changji City (44.0544N, 87.2262E), Shiho city (Wusu - 44.431N, 84.672E). Source: Maxar via Google Earth

Figure 5: The same four mosques were significantly renovated between 2012 and 2016; all showed additions of a dome and two or four minarets

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

However, following Xi Jinping’s April 2016 speech at the National Religious Work Conference in which he called for the sinicisation of Chinese religion,23 this renovation work appears to have been halted.

Then, following Chen Quanguo’s ascension as Xinjiang Party Secretary in late 2016, the renovations made to these mosques were reversed. In some cases this resulted in the newly built domes and minarets being removed; in most cases, it resulted in the demolition of the entire structure. Three of the four randomly chosen mosques shown above have been entirely demolished since 2016, and one has had its Islamic architecture removed (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The same four mosque sites, showing that three of them have been demolished entirely and that the fourth had its dome and minarets removed by 2018

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

Case study: Land uses at the sites of demolished mosques

Of 187 destroyed mosques that we recorded, only 41 sites (22%) have been redeveloped for other purposes, according to the latest imagery available at the time of publication, in many cases nearly three years since demolition (figures 7, 8 and 9). The rest either remain bare ground (65%) or have been converted for agriculture or turned into roads or car parks (12%).

Most mosques that were demolished between 2017 and 2020 weren’t razed to make way for new buildings, but instead were simply demolished and left as vacant land.

Figure 7: A mosque in Hotan’s Karakash County, before and after 2017

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

Figure 8: A mosque in Bayingol’s Lopnur (Yuli) County, before and after 2017

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

Figure 9: A mosque in Chochek’s Shiho (Wusu) city, before and after 2017

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

The vast majority of mosque demolitions have been targeted desecrations in which surrounding buildings have remained intact, but there are some examples in which a mosque has been retained while surrounding residential buildings have been razed (Figure 10). Eighty per cent of mosques in the latter category are in Urumqi.

Figure 10: A mosque in Urumqi’s Saybagh district that remained in 2019 following the demolition of the residential community that it had served

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

Case study: The demolition and miniaturisation of Kargilik’s Grand Mosque

A bizarre trend that has occurred in a small number of damaged mosques is the demolition of the Islamic-styled gatehouse and its reconstruction at a miniaturised scale. These mosques are generally significant and historic sites afforded significant degrees of formal protection.

For example, the Grand Mosque in Kashgar’s historic Kargilik County (Yecheng) was built in 1540.

In the 2000s, it was designated as a Xinjiang regionally protected cultural heritage site—the second highest level of protection granted to historic relics. Figure 11 shows the mosque as it once appeared (probably during the 1990s).

Figure 11: Kargilik’s Grand Mosque gatehouse as it appeared in the late 20th century

Source: Anon, “Yecheng kagilik jame,” Mapio Net, nd., online.

The historic Islamic architecture is clear: large domes and crescent moons at the top, colourful tile mosaics typical of Central Asian mosques, and the Shahada (Islamic creed) above the entranceway.

The Islamic features remained on the mosque, although somewhat faded, until the 2017 crackdown (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Kargilik’s Grand Mosque gatehouse in the 2010s

Source: Anon, “Kargilik’s Jame Mosque,” Mapio Net, nd., online.

Following the crackdown, most of the mosaic artwork was painted over, the Arabic writing was removed, the crescent moon motif was removed or replaced, and a large government propaganda banner hung from the mosque. Figure 13 is a photo taken in September 2018 by a visiting tourist, shortly before the gatehouse was razed. The mosque has a large red banner saying ‘Love the party, love the country’ draped across the building and a sign where the Shahada used to sit saying that CCP members, government employees and students are prohibited from praying in the mosque, including during the Eid festival. Furthermore, the doors were also closed and seemingly padlocked.24

Figure 13: Kargilik’s Grand Mosque gatehouse in September 2018

Source: YY, “Kargilik Mosque (加满清真寺),” Flickr, 11 September 2018, online.

Shortly after this photo was taken, the historic entranceway was demolished. By April 2019, it had been poorly reconstructed at roughly a quarter the original size (figures 14 and 15). Originally, the entranceway was roughly 22 metres across; the reconstruction is only 6 metres across. Much of the original site has been replaced by construction for a new shopping mall.

Figure 14: Kargilik’s Grand Mosque gatehouse rebuilt at a smaller scale in 2019

Note: This image has been slightly manipulated to avoid revealing potentially identifiable information about the photographer, who privately shared this image with ASPI. No architectural features have been changed from the original image.

Figure 15: Satellite imagery showing Kargilik’s Grand Mosque in September 2018 and April 2019; red arrowhead points to the miniaturised gatehouse

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

Although ‘miniaturisation’ was relatively rare across Xinjiang, it was noted in several significant mosques in Kashgar, including in Kargilik and Yarkant.

Sacred public sites

Scattered across Xinjiang’s vast open spaces are a number of sacred spaces. The region’s oases have supported lives and communities for centuries. Uyghurs and other Turkic communities in what the Uyghurs call Altishahr (ئالتە شەھەر ), or the ‘six cities’ in the south of Xinjiang, have followed Islam for over 1,000 years and have cultivated a unique fusion of Sunni fellowship and Sufi cultural and religious traditions.25

The mysticism that influences Uyghur Sufism draws on a cultural connection to land and the sacredness of place, in which holy sites (often the locations of purported miracles or the burial places of enlightened scholars, leaders, poets, saints, mullahs or sheiks) retain their sacrosanctity indefinitely.

For the devout, these sites are a source of healing, of introspection and of good fortune. The sites are an integral part of Uyghurs’ cultural history and connection to the land.26

Since 2017, as the state began systematically restricting personal expressions of Islamic culture and belief in Xinjiang, the sacred sites of Uyghur identity have been desecrated and destroyed in large numbers. Rian Thum notes that access to most mazar (shrine) sites had already been locked off to pilgrims and visitors over the past decade, and that their subsequent ‘destruction appears to have been an end in and of itself’.27

Across Xinjiang’s five southernmost prefectures, we located 349 sacred sites, 103 of which were formally registered as protected cultural heritage by the Chinese Government at various levels.28

Of all the significant and sacred spaces we examined, we found that 30% have been entirely demolished, including sites of famous pilgrimages. A further 27.8% have been damaged in some way (Figure 16).

Figure 16: The rates of damage to the various sacred and significant cultural sites surveyed in this report, by level of protection

Source: ASPI ICPC; the raw numbers are online.

Formal protection by the authorities has affected the rates of demolition: 51.4% of protected sites are undamaged, compared to only 38.2% of unprotected sites. Likewise, formally protected sites are about half as likely to have been entirely demolished than unprotected sites: 17.4% of formally protected sites were demolished outright, compared to 35.4% of unprotected sites.

We also found relatively high rates of destruction among nationally and regionally protected sacred sites: 16.7% of the nationally protected sites we examined had been destroyed, and 41.6% were damaged (totalling 58.3% damaged or destroyed). Likewise, 16% of sites protected at the Xinjiang regional level had been destroyed, and an additional 32% had been damaged in some way (totalling 48% damaged or destroyed).

However, formal protection neither applies to nor provides protection to the most significant sites.

Several of the most well-known and culturally significant sites, such as Imam Jafar Sadiq Mazar and Imam Asim Mazar, and potentially Ordam Mazar, that previously hosted major annual pilgrimages are offered no formal protection and have all been demolished by Chinese authorities since 2017.29

In many cases where significant graves remain, satellite imagery reveals that attached mosques and prayer halls have been demolished, apparently to deny access to and space for worshippers. Additionally, in many cases otherwise undamaged sites appear to have installed security checkpoints at the entrances or have been fully enclosed by walls, restricting access.

Case study: The destruction of Ordam Mazar

Ordam Mazar ( ئوردىخان پادىشاھىم , ‘Royal City Shrine’) was a small settlement of about 50 structures in the Great Bughra desert (Figure 17). Sitting midway between Kashgar and Yarkant it was surrounded by miles of desert and was commemorated as the place from which Islam spread across the region.

It marked the site where, in 998 AD, Ali Arslan Khan, the grandson of the first Islamic Uyghur king, died in a battle to conquer the Buddhist kingdom of Hotan. Ali Arslan’s martyrdom was marked by a festival every year, drawing Uyghur pilgrims from all over southern Xinjiang at the beginning of the 10th Islamic month of Muharram.30

Figure 17: A 2013 satellite image of Ordam Mazar

Source: Airbus via Google Earth.

Tens of thousands of people visited the site before the festival was outlawed in 1997,31 the year before the 1,000th anniversary of Arslan Khan’s death. Since then, the area has been locked down. The religious curators of the site have mostly been pushed away, and only one family remained at the shrine by 2013: the family of Qadir Shaykh (Figure 18). He was required to report all unauthorised visitors to authorities, and most devotees who visited in the years preceding 2017 did so in the middle of the night to avoid identification.32 Their worship would only be betrayed by the presence of a new flag of prayers tied to the bundle of sticks that is often used to mark a sacred site (tugh,تۇغ ).

Figure 18: A photo of Qadir Shaykh taken by a visiting tourist in 2008

Source: ‘Left-behind elderly in the depths of the desert, accompanied by a falcon when living alone’ (沙漠深处的留守老人独居时与猎鹰为伴), WeChat, 8 April 2015, online.33

The official closure of Ordam Mazar in 1997 was justified by the banning of illegal religious activities (非法宗教活动) and feudal superstition (封建迷信), which linked the mystic traditions of the Uyghur people to notions of backwardness and mental illness.34 Ordam Mazar and its connection to mystic expressions of Islamic faith became emblematic of the ‘Three Evils’ (三股势力) of terrorism, separatism and religious extremism. The alleged linkage propelled the Chinese Government’s crackdown in Xinjiang and provided ideological justification for the erasure and alteration of sacred indigenous sites.

Our analysis of satellite imagery found that, between 24 November and 24 December 2017, the entire site of Ordam was razed (Figure 19). The following autumn, Altun Rozam ( ئالتۇن روزام ), a shrine formed from a bundle of sticks and flags that lay 1.2 kilometres northwest of Ordam and marked the sand dune where Arslan Khan is said to have been killed in battle 1,020 years ago, was bulldozed (Figure 20).

The stone foundations have been covered by the sand, and now no sign of the sacred town remains.

The whereabouts of Qadir Shaykh and his family are unknown

Figure 19: Ordam Mazar in May 2018, showing the nearly complete destruction of the desert outpost

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

Figure 20: Photo of what appears to be the cultural relic preservation marker for Ordam Mazar in 2013

Source: Rita@kashi weifeng, ‘Pathfinder to the Desert Holy Land: Ordam, a tomb of king’ (探路沙漠圣地--奥达木王陵), Douban, 22 May 2013, online.

Ordam marks the endpoint of a 15-day pilgrimage route, which for centuries connected sacred sites in and around the Great Bughra desert. All the pilgrimage stops on this route were also demolished in late 2017; including Häzriti Begim Mazar, which was a shrine marking the location where Häzriti Begim, the son of Rome’s emperor, died in battle alongside Arslan Khan.35

The remoteness of Ordam Mazar and other stops along this pilgrimage route is significant. Ordam is roughly 15 kilometres from the nearest cultivated area and 35 kilometres from the nearest county centre (Figure 21). Given the level of surveillance in Xinjiang, including new networks that have been built since the 2017 crackdown, the demolition of these pilgrimage sites was not necessary to prevent worshippers visiting them.

Likewise, considerable investment is needed to transport a demolition team across tens of kilometres of ungraded desert tracks, mostly crossing sand dunes. Therefore, this suggests that the demolition not only represents the curtailing of religious freedoms in Xinjiang, but also the deliberate severing of ties that Uyghurs have to their cultural heritage, history, landscape and identity.

Figure 21: A photo of part of Ordam town, showing the mosque, taken by a visiting tourist in 2017

Source: Mo de shijie (蓦的世界), ‘Exploring the mystery of Aodamu (Audang) Mazha’ (奥达木(奥当)麻扎探秘), Weixin, 25 March 2017, online.

Ordam’s demolition also marks the end of Dr Rahile Dawut’s public life. Dawut is an ethnographic scholar and an international expert on Xinjiang’s sacred sites. The New York Times described her as ‘one of the most revered academics from the Uyghur ethnic minority in far western China’,36 and her previous work on Ordam Mazar was funded by the Chinese Government and its academic grants.37

In December 2017, the same month that Ordam was demolished, Rahile Dawut went missing while trying to travel to Beijing for a conference. Her whereabouts remain unknown. Her family and relatives believe that she was forcibly ‘disappeared’ and arbitrarily detained somewhere in the vast network of more than 375 ‘re-education’ centres, detention camps and newly expanded prisons in Xinjiang.38

Her ‘crimes’ or ‘misdemeanours’ have never been made public. Dawut is one of at least 300 Uyghur intellectuals detained in Xinjiang since 2017.39

The demolition of Ordam Mazar and the disappearance of a world-renowned researcher of Uyghur sacred spaces highlights the extent that Xinjiang’s public spaces of faith and identity have been targeted and outlawed. This highly sacred site for the Uyghur people, which had fought back the desert and multiple rounds of conquest for over 1,000 years, has now been subsumed back into the desert.

Case study: The desecration of Aksu’s sacred cemetery

Near the Yéngichimen village in Toyboldi ( تويبولدى ) township, about a four-hour drive from Aksu city, lay the remains of Mulla Elem Shahyari ( شەھيارى ). Shahyari was a notable poet and Islamic leader around Aksu in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In his youth, he studied Islamic oratory, and he eventually became a chief poet for the ming-begi (local chieftain, مىڭ بېگى ).40

He is known for his long poem, composed over 10 years, ‘Rose and Nightingale’ ( گۈل ۋە بۇلبۇل ). In 1814, after he died from illness in his home town at Toyboldi, his grave became a shrine. The grave was near the entrance of a 13-hectare cemetery, in the yard of the cemetery’s prayer hall (Figure 22).41

Figure 22: Yéngichimen cemetery in 2014 and 2019, showing its destruction

Source: Maxar via Google Earth.

As a child, Aziz Isa Elkun, a now-exiled Uyghur poet who grew up nearby, revered Shahyari’s shrine; the village considered Shahyari to be enlightened. During an interview with ASPI, Mr Elkun said:

[Our] Islamic and Uyghur cultural identities … are intrinsically linked; therefore [we] regard [Shahyari’s] burial place as a holy place that connects the spirits of the generations past and today … [The] graveyard is a symbol of bonding for the Uyghurs spiritually, culturally and politically.42

With many of his fellow townspeople, he visited the grave of Shahyari every Friday and after religious holidays, praying in front of the tomb:

I read Mulla Elem Shahyari’s best known poem ‘Rose and Nightingale’ when I was a teenager … After reading his poetry, it inspired me to learn Uyghur classic literature and poetry. Since then, I started writing poems and had them published in local newspapers and journals.43

The last time he visited Shahyari’s shrine was the last time he returned home in February 2017. During that visit, the shrine was in serious disrepair, and the authorities were prohibiting locals from repairing the grave (Figure 23).

Figure 23: A photo of Mulla Elem Shahyari’s Mazar, taken in 2009

Source: Cultural Relics Bureau of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (新疆维吾尔自治区文物局), Immovable cultural relics: Aksu area, volume 1 (不可移动的文物 阿克苏地区卷1). Urumqi: Xinjiang meishu shying, 2015, p. 537.

Mr Elkun left Xinjiang in 1999, but his family stayed behind, mostly living in Yéngichimen village. In 2017, Mr Elkun’s father, Dr Isa Abdulla, was laid to rest after a life in the vicinity of Shahyari’s shrine, within 150 metres of it in a cemetery plot prepared by the family several years previously (Figure 24). Unable to return home, or even contact his relatives without risking their punishment, Elkun was forced to mourn from afar, finding his father’s grave on satellite images.

Figure 24: Dr Isa Abdulla’s gravesite, before its demolition

Source: Matt Rivers, ‘More than 100 Uyghur graveyards demolished by Chinese authorities, satellite images show’, CNN, 3 January 2020, online.

However, less than nine months after his father’s death, local authorities in Aksu Prefecture began re-engineering the cemetery. In August 2018, lines of new numbered graves were constructed over a corner of the cemetery. According to official documents and state media reports, the numbered graves are referred to as ‘public welfare ecological cemetery graves’ (公益性生态公墓建设).

Chinese Government officials say that they’re ‘standardising’ and ‘civilising’ public cemeteries in the name of social stability, rural revitalisation and ecological protection while preventing ‘random burials’ and relocating old graves.44 The new graves would eventually cover 1.5 hectares of the old cemetery.

Dr Isa Abdulla’s grave is now unmarked, save for the number 47, and is now otherwise identical to dozens of white clay-brick graves in 39 identical rows (figures 25 and 26).45

Figure 25: Isa Abdullah’s wife and daughter mourn at his new grave in a Chinese state media propaganda report

Source: ‘By following CNN, we find how they make fake news about Xinjiang’, CGTN, 13 January 2020, online.

Figure 26: Toyboldi’s new ‘public welfare ecological cemetery’

Source: ‘By following CNN, we find how they make fake news about Xinjiang’, CGTN, 13 January 2020, online.

The new graves covered only slightly more than 10% of the original cemetery. In early February 2019, the remaining graves, spread over 11 hectares, were levelled, according to satellite imagery analysis.

None of the original graves remains. Although the garden of the mosque, where Shahyari’s shrine sat for hundreds of years, hasn’t been bulldozed, the shrine itself has been demolished.

In 2020, the site was visited by reporters from the Chinese state media outlet CGTN, who filmed the bulldozed and barren remains of the cemetery (Figure 27).46

Figure 27: The grounds of Yengichimen cemetery after being cleared of graves

Source: ‘By following CNN, we find how they make fake news about Xinjiang’, CGTN, 13 January 2020, online.

The CGTN report claimed that Dr Isa Abdullah’s family requested that his body be moved before the original gravesite was demolished. The mechanism of exhumation requests is unknown in this case.

However, a 2019 community notice posted at another to-be-bulldozed cemetery near Hotan gave relatives just three days to register and request the exhumation and relocation of their loved ones’ remains; otherwise, the remains would go unclaimed (Figure 28).47

Figure 28: Public notice of tomb relocation in Hotan

Note: This Uyghur notice states: ‘Notice of relocation of the tomb of Hotan Sultanim Mazar. To the people of the city: In accordance with the needs of our city’s urban development plan and the spirit of the legislation of the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the Autonomous Region on further standardisation of the management of burial places and cemeteries in our autonomous region, as well as the requirements for creating a comfortable environment for the general public, it is decided to relocate corpses from Sultanim Mazar into Imam Muskazim Mazar of the Hotan Prefecture. Therefore we ask the owners of the graves to register at Sultanim Mazar between 18 March 2019 to 20 March 2019. Any graves without registration will be considered as unclaimed graves and will be relocated automatically. A delayed response will be responsible for all the consequences. Please send this notification to others.’ Translation by ASPI.

Source: Bahram Sintash, Demolishing faith: the destruction and desecration of Uyghur mosques and shrines, Uyghur Human Rights Project, October 2019. online.

The policy of demolishing traditional cemeteries and replacing them with ‘public welfare ecological cemeteries’ has been widely adopted throughout Aksu Prefecture. Standardised management of cemetery grounds was adopted in June 2016, and ‘complete coverage’ of numbered clay graves was to be achieved by the end of 2019, according to local media reports.48

Of 26 rural shrine and cemetery complexes that we located in Aksu through satellite imagery analysis, 22 (85%) had had most or all of their graves demolished by 2020, and 15 (58%) of cemeteries had had traditional graves replaced with rows of clay-brick graves (Figure 29).49

Figure 29: Mardan Mugai, Deputy Secretary of Aksu Prefecture’s Party Committee, and other members of the local government standing beside a ‘public welfare ecological cemetery’ construction site

Source: ‘At the end of 2019, the Aksu area has basically achieved full coverage of the construction of public welfare ecological cemeteries’ (2019年底阿克苏地区基本实现公益性生态公墓建设全覆盖), Aksu News Network (阿克苏新闻网), 20 May 2016, online.

In a 2016 speech, the Deputy Secretary of Aksu Prefecture’s Party Committee, Mardan Mugai, called on government departments to ‘waste no time in guiding the masses … to change their customs’ and ‘abandon closed, backwards, conservative and ignorant customs’, 50 referring to traditional cemeteries and burial grounds in the prefecture, including sacred sites and shrines.

An August 2018 state media report claimed that the ‘rectification’ of traditional cemeteries had been implemented in 235 cemeteries across Aksu by the end of July and that the construction of 174 ‘public welfare ecological cemeteries’ had begun.51

Our evidence suggests that this policy has continued unabated since 2018 and that the number of cemeteries with graves demolished and new ‘ecological cemeteries’ built is likely to be roughly double the figure stated above.52

The demolition of spiritual sites in Xinjiang’s Aksu Prefecture represents the forcible severing of ties between Uyghur communities and their history and landscape. Aziz Isa Elkun characterised Shahyari’s shrine and the attached cemetery as the lifeblood of the village, saying, ‘The entire community was connected to that graveyard’ and that it was a place to pray.53

A Uyghur academic we spoke to while writing this report emphasised the importance of cemeteries to the public life and personal identity of Uyghurs and other non-Han nationalities in Xinjiang. The cemeteries, in their words, are ‘a material and symbolic representation of the collective claim to a place, a land and a homeland’.54

Major cemeteries ‘play a significant role in bonding the past and present’. For this individual, China’s new assault on cemeteries is more than the physical removal of sacred areas; it’s an attack on one of the last remaining aspects of Uyghur public life tolerated by Chinese authorities:

Arguably … until this campaign began, [cemeteries] had been the only part of Uyghur physical space, life and culture that hadn’t been tainted by large-scale CCP political imposition … In this sense, the demolition of cemeteries isn’t just an attack on Uyghurs’ claims to ancestral land … it is also a calculated effort to sever the emotional and blood ties to the past.55

Earlier this year, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry said, in response to concerns raised about the destruction of traditional cemeteries, that ‘Xinjiang fully respect[s] and guarantee[s] the freedom of all ethnic groups … to choose cemeteries, and funeral and burial methods.’56 However, widespread evidence collected by ASPI and other researchers, including satellite images and statements from officials in Xinjiang, shows that to be untrue, as traditional cemeteries are being subjected to a systematic campaign of desecration.

Background: sinicising Xinjiang under Xi Jinping

The Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities are no longer trusted with autonomy or their own cultural traditions but rather must actively embrace the cultural traditions and practices of their Han colonisers.57 This process of incorporation involves both the effacement of certain aspects of minority culture and the reshaping of local cultures and landscapes in order to more firmly stitch them into the national story.

The religious and foreign elements of non-Han cultures are viewed with particular suspicion by government officials.58 At the National Religious Work Conference in April 2016, Xi Jinping stressed the importance of fusing religious doctrines with Chinese culture and preventing foreign interference.

‘The ultimate goal [of religious work]’, the CCP’s top religious policy adviser Zhang Xunmou stated in 2019, ‘is to achieve its complete internal and external sinicisation.’59

In recent years, the Chinese Government has strengthened its control over religion, passing a revised set of regulations monitoring religion in 2017 and subsuming the state body managing religious affairs into the CCP’s United Front Work Department (UFWD) in 2018.60

Despite the fact that Xinjiang was designated a Uyghur autonomous region in 1955, Xinjiang is now spoken about as a location of ‘cultural integration’, where different peoples, religions, and cultures have long ‘coexisted’, ‘blended’ and, ultimately, fused together.61 This is despite the fact that Uyghurs and other Turkic or Muslim minorities made up roughly 59% of the XUAR’s population in 2018,62 and nearly 60% of Xinjiang’s 25 million residents practise some form of Islam.63

The Chinese state recognised the importance of documenting and protecting the ‘excellent traditional ethnic cultures’ (优秀传统民族文化) of Xinjiang in a 2018 government White Paper, but also stressed the need to ‘modernise’ and ‘localise’ the ethnic cultures while insisting that ‘Chinese culture’ is the ‘bond that unites various ethnic groups’.64 Foreign reporters on state-sponsored trips to Xinjiang are told Uyghurs are ‘immigrants’ to Xinjiang and that Islam was imposed on Uyghurs by foreigners.65

That ethos was outlined in a 2019 state media editorial by hardline public intellectual Ma Pinyan, who claims the various ethnic cultures of Xinjiang have been ‘nurtured’ in the ‘bosom’ and ‘fertile soil’ of Chinese civilisation and culture: ‘Without Chinese culture, the culture of any other ethnic group would be like a tree without roots and water.’66 In this telling, Xinjiang culture wasn’t synonymous with Islamic culture; rather, Uyghur culture, in particular, ‘originated from Chinese culture dominated by Confucianism’.67

In Xinjiang, officials have cracked down on ‘illegal’ or ‘abnormal’ religious practice among the Uyghurs and other Muslims since 2009, outlawing ‘illegal religious activities’ as they tightened controls over Islamic education, worship, fasting and veiling.68 Islamic-sounding names were banned,69 and ‘extremist’ religious materials (Qurans, prayer mats, CDs etc.) were confiscated70 and, in one case, appear to have been burned in public.71

In 2014, the former Executive Director of the UFWD,72 Zhu Weiqun, blamed ‘religious fanaticism’ (宗教狂热) for unrest in Xinjiang and called for ‘persisting with the trend towards secularisation’ within Xinjiang society in a state media interview.73 In 2017, the XUAR passed a comprehensive set of regulations to guide ‘deradicalisation’ work across Xinjiang—a set of rules that was revised in October 2018 to retrospectively authorise the mass detention of Uyghurs in ‘re-education’ camps.74

Xinjiang officials now warn against the ‘Halal-isation’ (清真泛化),75 ‘Muslim-isation’ (穆斯林化),76 and ‘Arab-isation’ (阿拉伯化)77 of religious practices in Xinjiang and seek to actively ‘rectify’ any practices, products, symbols and architectural styles deemed out of keeping with ‘Chinese tradition’.78

Tighter control over mosques and religious personnel is central to the plan to sinicise Islam in Xinjiang, as is the ‘rectifying’ of places of religious worship. Wang Jingfu, head of the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee in Kashgar city, told Radio Free Asia in 2016:

We launched the rectification campaign with the purpose of protecting the safety of the worshippers because all the mosques were too old. We demolished nearly 70% of mosques in the city because there were more than enough mosques and some were unnecessary.79

Under the UFWD’s ‘four entrances campaign’ (‘四进’清真寺活动), mosques across Xinjiang are required to hang the national flag; post copies of the Chinese Constitution, laws and regulations; uphold core socialist values; and reflect ‘excellent traditional Chinese culture’.80 Architecturally, this involves the removal of Arabic calligraphy, minarets, domes and star-and-crescent and other symbols deemed ‘foreign’ and their replacement with traditional Chinese architectural elements.81

Finally, the control and sinicisation of Xinjiang also advances the state’s economic agenda through commodified and curated tourism and the promotion of Xinjiang as a key node in Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative.82

Cultural heritage and the role of UNESCO

The global bodies charged with the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide have been silent on cultural destruction in Xinjiang. The Chinese Government has worked closely with UNESCO after ratifying the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in 1985 to develop its capacities for preservation work.83

There’s been a sustained, top-down effort involving all levels of the Chinese Government to expand the formal recognition of Chinese cultural sites and intangible culture on the world stage and to deepen China’s involvement and influence in UNESCO,84 pre-dating, and assisted by, the US decision to reduce funding and withdraw from UNESCO in 2017.85 China’s representative, Qu Xing, is the organisation’s current Deputy Director-General.86

Evidence of those efforts came in 2019, when the total number of Chinese UNESCO World Heritage sites reached 55, making China the country with the most such sites.87 Cultural heritage is not only a soft-power asset for the Chinese state but also a tool of governance. Rachel Harris reminds us:

It can be used to control and manage tradition, cultural practices, and religion and to steer people’s memories, sense of place, and identities in particular ways, providing a softer and less visible way of rendering individuals governable.88

Two Uyghur cultural practices are listed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage register: the 12 muqam,89 inscribed in 2005; and the mäshräp,90 inscribed in 2010.

However, both these diverse and rich cultural practices, which involve song, dance and storytelling, have been co-opted and politicised by the Chinese Government. Mäshräp has been stripped of its religious content and is now used to counter extremism,91 while muqam has been commodified, rewritten and secularised for safe consumption.92 Meanwhile, well-known Uyghur performers of traditional Uyghur music, such as Abdurehim Heyt and Sanubar Tursun, suddenly disappeared from public life in 2017 and 2018 before resurfacing under mysterious circumstances.93

UNESCO, which is an organisation founded to ‘promote the equal dignity of all cultures’ and ‘in response to a world war marked by racist and anti-semitic violence’,94 has made no public comment on the abuses perpetrated against Xinjiang’s minorities by the Chinese state.

Similarly, UNESCO’s advisory body dedicated to protecting ‘cultural heritage places’, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), has been silent on the destruction of cultural heritage in Xinjiang while publicly condemning, for example, Turkey’s decision to ‘reverse the status of Hagia Sophia from a museum to a mosque’ in July 2020.95 In 2009, the US branch of ICOMOS publicly expressed concern about the demolition of much of the old city of Kashgar,96 but it’s been silent since then.

For over a decade, the World Monuments Fund, a New York based non-profit, has trained Chinese conservators and helped to fund the renovation of the Forbidden City and the Great Wall, while doing nothing to stop the wanton cultural destruction in Xinjiang.97

ASPI repeatedly sought comments from UNESCO and ICOMOS about their public position on Xinjiang and the Uyghurs but received no response.

These organisations must re-examine their mission. Their failure to investigate or comment on the destruction of indigenous culture in Xinjiang suggests their capture by or subservience to Beijing.

Conclusion and recommendations

The Chinese Government’s sinicisation policies in Xinjiang have led to the destruction of thousands of mosques and hundreds of sacred cultural sites. These acts of intentional desecration are also acts of cultural erasure. The physical landscape—its sacred sites and even more prosaic structures—holds the memories and identities of local community and ethnic groups. ‘Memory floats in the mind’, eminent historian R Stephen Humphreys remarked in 2002, ‘but it is fixed and secured by objects.’98

The Chinese Government’s destruction of cultural heritage aims to erase, replace and rewrite what it means to be Uyghur and to live in the XUAR. The state is intentionally recasting its Turkic and Muslim minorities in the image of the Han centre for the purposes of control, domination and profit.

The Chinese state has long sought to ‘transform’ and ‘civilise’ Xinjiang, but Xi Jinping and his lieutenants bring a new sense of urgency to this colonialist project. Under the guise of combating perceived ‘religious extremism’ and promoting ‘inter-ethnic mingling’, Chinese officials are slowly but systematically stripping away those elements of Uyghur culture they deem to be ‘foreign’, ‘backward’, ‘abnormal’ or simply out of sync with Han-centric norms. What remains is a Potemkin village: sites and performances for tourist consumption and propaganda junkets.

Unlike the international condemnation that followed the Taliban’s dynamiting of the Bamyan Buddhas in Afghanistan99 or the destruction of parts of Dubrovnik and Sarajevo following the collapse of Yugoslavia,100 China’s acts of cultural erasure in Xinjiang have been perhaps less dramatic and visible, yet arguably far more wide-ranging and impactful.

In the light of this report’s findings, ASPI recommends as follows:

- The Chinese Government must abide by Article 4 of its own Constitution, allow the indigenous communities of Xinjiang to preserve their own cultural heritage and protect the freedom of religious belief outlined in Article 36, and not in ways that are defined and controlled by authorities who appear to have the opposite motive. It must uphold the autonomous rights of its non-Han communities to protect their own cultural relics and heritage under the 1984 Law on Regional Ethnic Autonomy and cease the demolition of significant cultural and religious sites in the XUAR.

- UNESCO and ICOMOS should immediately investigate the state of indigenous cultural heritage in Xinjiang and, if the Chinese Government is found to be in violation of the spirit of both organisations, it should be appropriately sanctioned. Both organisations must make public statements on the cultural erasure in Xinjiang, drawing on our investigations and other existing research.

- National governments should apply public pressure to UNESCO, ICOMOS and other conservation bodies if they fail to respond to Uyghur cultural destruction in Xinjiang.

- International cultural and heritage organisations such as UNESCO and ICOMOS must shift from silence on cultural erasure in Xinjiang to a coordinated approach with the global human rights network, which is already engaged in bringing international pressure to bear on Chinese authorities in ways relevant to the missions of UNESCO and ICOMOS.

- Governments throughout the world, including governments of developing and Muslim-majority countries, must speak out and pressure the Chinese Government to end its genocidal policies in Xinjiang, stop the deliberate destruction of indigenous cultural practices and tangible sites, and consider sanctions or even the boycotting of major cultural events held in China, including the 2022 Winter Olympics.

Appendix: Full methodology

For both datasets, the basic methodological aim was the creation of a new, unbiased, stratified dataset of locations of mosques and sacred sites before the 2017 crackdown. Those locations were then checked against recent satellite imagery to ascertain their current status.

Mosques

The Chinese Government’s 2004 Economic Census identified nearly 24,000 mosques in Xinjiang.101

Accordingly, it wouldn’t be feasible to manually examine every site and ascertain its current status following the 2017 crackdown. Therefore, in order to estimate the number of mosques damaged and destroyed in Xinjiang, we needed to build our own dataset of suitable sample sites and then extrapolate the results across the region.

For valid extrapolation, it was crucial to obtain a nearly random sample of Xinjiang’s mosques. Therefore, any previously created lists of demolished mosques needed to be completely ignored.

Instead, we needed to create a novel database free of any sampling bias. The most complete source of this data would be through official Chinese Government information; however, there are significant barriers to access to and use of that information.

The data from the 2004 Economic Census provided addresses for each of the nearly 24,000 mosque sites in Xinjiang;102 however, in many cases, the addresses are imprecise and couldn’t be clearly associated with physical buildings visible in the satellite imagery. Therefore, we used a combination of two different methods.

First, an aggregated database of 10,000,000+ points of interest (POIs) across China was obtained. The POIs primarily represented businesses, amenities or attractions located with high precision, largely for inclusion into national navigation and online map platforms. An example of the density and precision of the POIs is shown in Figure 30 as a screenshot of a map of part of the regional capital, Urumqi.

Figure 30: A map showing the full POI database consulted (not queried for mosque) across a neighbourhood in Urumqi

Source: ASPI ICPC.

The database was queried for the word ‘清真寺’ (mosque). That yielded 1,733 mosques nationwide, including 289 in Xinjiang. Of those, 16 were excluded due to their current status or location being unclear or due to being duplicate results, leaving 273.

A visual examination of the mosques found through this method showed varied results for the size and prominence of the mosques, along with their locations (rural or urban). Mosques in Urumqi were overrepresented compared with those in other prefectures. This bias was accounted for by the prefecture-based extrapolation explained below.

For purposes of comparison, the database was also queried for the terms ‘教堂’ (church) and ‘庙’ (temple). Those queries yielded 14 and eight results, respectively (representing 13.6% and 16.6% of all sites of those denominations in Xinjiang when compared to the 2004 Census). Of those, none had been damaged or demolished.103

Additionally, we conducted a systematic visual search of mosques using pre-2017 satellite imagery.

That was done by selecting three search locations for each county: one in the county centre, one in a randomly selected township centre and one in a randomly selected village.104 Each search point was expanded into a circle with a 2.5-kilometre radius to define a search area.

That resulted in 307 search areas. Mosques were found in approximately 70% of the areas; the 94 remaining search areas generally had inadequate satellite imagery to ascertain the location of the mosque, or had no clearly discernible mosque in the search area.105 Finally, duplicates were removed.

Later, we removed mosques for which recent satellite imagery was unavailable and the current status of which couldn’t be ascertained.106 That left a total of 192 mosques found through this method.

The dataset was completed using only pre-2017 imagery to avoid accidental bias towards demolished mosques (for example, through structures suspected to be mosques being ‘confirmed’ as mosques by their demolition).

Finally, a second POI database from AutoNavi was queried for mosques. That found an additional 73 mosques, of which 67 were unique and not duplicates of previously examined mosques.

Together, using these two methodologies and three datasets, we found a total of 533 unique mosques, representing 2.25% of the official total in the region. A map of all mosques in our pre-2017 dataset is included in Figure 31.

Figure 31: The distribution of mosques located as part of the pre-2017 dataset

Source ASPI ICPC.

Once we compiled the pre-2017 dataset of mosque locations, each one was then visually compared to recent satellite imagery (generally mid-2019 to 2020). We recorded its current status, changes since 2017 and, where available, date ranges for the demolition or removal of Islamic architecture.107 For undamaged sites, we recorded the date of the last available satellite imagery so that follow-up studies can be prioritised to look at the ‘oldest’ sites. We generally accessed satellite images via Google Earth; where Google Earth didn’t have sufficient satellite imagery, we used other commercial sources with 30–50-centimetre resolution.

In some cases, we based the distinction between ‘slightly damaged’ and ‘significantly damaged’ on an assessment of how important the removed features were to the mosque’s structure and aesthetics.

For example, a mosque with only a small dome that had been removed would be coded as slightly damaged, despite the fact that all Islamic architecture on the structure had been removed, as the dome wasn’t a significant element in the building’s earlier aesthetics.

Those results were then tabulated by prefecture and current status. Eleven prefectures had over 2.5% of their total mosques represented in our sample.

We performed statistical tests against the data to determine any predictive variables, including population density, distance from county centre, distance from prefectural city, percentage of minority population and latitude. None of those tests showed significant responses to rates of damage and demolition. The variables are available on request to researchers who want to explore potential correlations further.

Extrapolation for the total number of destroyed and damaged mosques across Xinjiang was done at the prefectural level, which accounted for the majority of variation within the sampled data. For the 11 prefectures that were represented by over 2.5% of their total mosques, we directly extrapolated using the sampled data; for example, in Urumqi, where 38% of mosques were sampled, 17% were destroyed, so we extrapolated that 17% of all mosques had been destroyed.

For the remaining prefectures with under 2.5% of all mosques sampled, the extrapolation was guided equally, using both the prefectural rates of destruction and the Xinjiang-wide rates (excluding Urumqi, an outlier in our sample and dramatically overrepresented). For example, if a prefecture with fewer than 2.5% of mosques sampled had 40% of all sampled mosques destroyed, but the Xinjiang-wide rate was only 30%,108 it would be extrapolated that 35% of all mosques had been destroyed in the prefecture.

Cultural sites

We analysed shrines and other sacred sites in a similar manner. We selected and located a total of 251 culturally significant sites from Xinjiang’s Cultural Heritage Bureau’s 30-volume Immovable cultural relics encyclopedia.109 Our efforts focused only on southern Xinjiang, where the Uyghur population is concentrated, and traditional Uyghur cultural influences are more pronounced.

We selected sites for inclusion based on their assessed cultural significance with assistance from a Uyghur analyst, and where possible then found the exact location of those sites. Additionally, we queried a separate 6,000,000-point POI database obtained from academic sources for the term 麻扎 (mazar, ‘shrine’). That resulted in 131 points in the examined prefectures that could be confidently linked to a suitable location, such as a cemetery complex, mosque or shrine structure.

The inclusion of those points was considered important owing to the bias against Islamic sites in China’s official protection of heritage and was designed to expand our dataset to include sacred sites that aren’t formally registered or protected and that therefore don’t appear in the volumes we consulted.

This dataset was then compared against recent satellite imagery in the same manner that mosques were, and the same values were recorded. No extrapolation was done with this dataset to quantify the total numbers of damaged and destroyed sites beyond our sample due to the lack of information on the number of sites before 2017.

24 Sep 2020